By Gavan Bergin

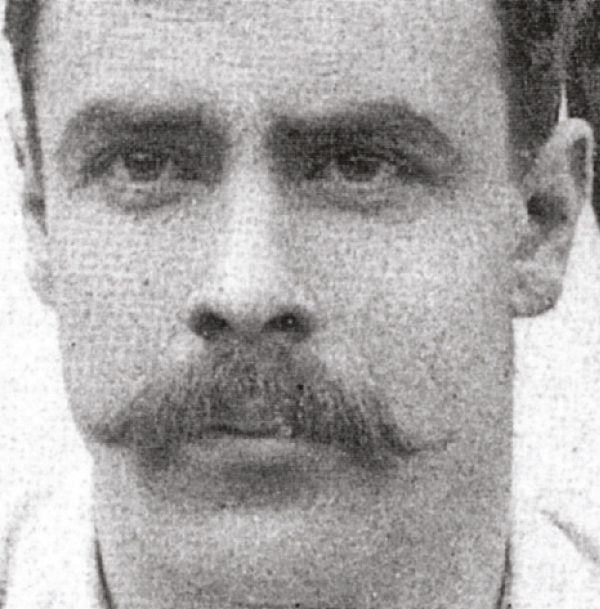

Archie Goodall was born in Belfast in 1864 and grew up in Kilmarnock in Scotland. As a boy he learned to play football along with his brother John, who went on to be an England international player.

In the early 1880s, Archie moved to England and began to make his name as a professional footballer, playing for Liverpool Stanley between 1885 and 1886. By that time, as well as having become a very good footballer, Archie had grown into, according to the Derby Telegraph, “a rambunctious powerhouse of a player, with a cast-iron body set on a pair of legs that seemed like oak trees, who knocked defenders aside with a barrelled chest before thumping the ball into the net with an anvil-like boot”.

Archie spent the 1887/88 season with Bolton Wanderers, then moved to his brother’s club Preston North End for the start of the 1888/89 season. That was the first ever season of the Football League and Archie made his debut playing at inside-forward in a 4-0 win against Wolverhampton Wanderers on September 18th 1888.

Two weeks after playing his first Preston game Archie was gone from the club, not due to his performance on the field – he had played brilliantly – but he was a tempestuous, exuberant fellow of a sometimes fiery temperament who had quite a high public profile due to his achievements outside of football.

He was a successful weightlifter and had an interest in the world of music hall, so he was pretty unconventional for a footballer of the time. Archie had a keen sense of his own worth, as a player and as a man, and he certainly wasn’t afraid to stand up for himself against the bosses. As a result, he often ended up coming into conflict with management at the football clubs he played for. He was transferred to Aston Villa on September 30th 1888. It was the Football League’s first ever player transfer.

In his first match for Aston Villa, against Blackburn Rovers, he played as a central defender yet still managed to score. He continued to do amazingly well for Villa in various different positions, playing at wing-half, full-back and centre-forward. He finished the 1888/89 season with an impressive record of seven goals in fourteen games. Nevertheless, at the end of the season he moved to Derby County.

Archie showed great improvement as a player after moving to Derby, perhaps due to the fact that he wasn’t moved about so much. At Derby, Archie played mostly as a defender and his hard-hitting style turned out to be just as effective as it was when he played up front. And he didn’t lose the knack of scoring, he began to earn a reputation for hitting the back of the net with spectacular long-range goals.

The Lancashire Times reported his arrival at Derby by praising him as “a bold-hearted, never-beaten player, with the finest long-shot in the kingdom, whose dash and spirit are contagious, and to his example of pluck and determination may be attributed the recent transformation of the Derby team. It is literally true to say of him that he is a strong defender, for he holds several records in competitive weight-lifting, in which he is probably unequalled in the Midlands. His physical power is greatly helpful to him in tackling opponents, he is a tremendous force, overflowing with energy, with methods that occasionally smack of the ultra-vigorous, and on his day is capable not only of holding the best centre forwards, but of playing the inside three men himself.”

Archie stayed with Derby for fourteen years. He was made club captain in 1899 and helped Derby to the greatest period of success they had ever had. The season before Archie joined, Derby had finished only four points above last place in the League, after he arrived they would achieve regular top-ten positions, including a runners-up spot and two third place finishes and in the FA Cup. Derby got to the semi-final in 1896 and 1897, then to the Final in 1898 and 1899. During his time as captain, several club records were set that remain unbroken to this day. As well as the team records, Archie set one as a player: he played 151 consecutive league matches for Derby, never missing a single game between 1892 and 1897.

In 1903, Archie left Derby after 443 matches and 52 goals. He joined Plymouth Argyle as their first ever captain, before moving on to Glossop Town, where he scored 13 goals in 28 matches – pretty impressive for any forward, never mind one who had turned forty the previous summer!

But, even then, the old warrior wasn’t quite finished, and he was signed up by Wolverhampton Wanderers for the 1905/06 First Division season. In December 1905, he set one last record in English football, in his last ever league match, for Wolves against Everton, at the age of 41 years and 153 days, making him the oldest man ever to play for Wolves.

Although Archie and his brother John Goodall both grew up in Scotland, neither of the brothers was allowed to play for the Scotland international team. As John was born in England, he was eligible to play for them, and he made his England debut in 1888. Archie had to wait much longer to play international football because, for the first seven years of its existence, the Ireland team consisted only of players who played for Irish club sides, which meant that Archie couldn’t play for the country of his birth.

The Irish Football Association eventually changed its restrictive selection policy and, when they played Wales on March 4th 1899, the Ireland team contained four players from English league clubs and one of those pioneering players was Archie, making his international debut at the age of 33!

He may have been a bit long in the tooth to be playing his first match for Ireland, but it sure didn’t show on the pitch. After a scoreless first half, Ireland went 1-0 up early in the second half, and for a while it looked like Archie’s first game at the heart of the Irish defence would be uneventful – until Wales came storming back to put heavy pressure on Ireland’s back line. Then Archie came into his own with a show of resolute defending that saved the day for Ireland, making sure the game was won and ensuring that there could be no recriminations about the selection of the English-based players.

His brilliance in the match did not go unnoticed in the papers, and The Freeman’s Journal reported that, “Archie Goodall played a magnificent game in defence, his tackling and pacing earned the admiration of the crowd, and he even managed to get forward, coming very close to scoring in the first half with a fast grounder of a shot. Throughout the game he was resolute, with his vigorous defending decisive in preserving the victory for the Irish team. At the end of the match the crowd grew wild in its enthusiasm, spectators jumped the palings, swarmed around the victorious players and carried Goodall shoulder high to the pavillion.“

In 1903 Ireland’s last match of the British Championship was against Wales. A win would make it the best season ever by any Irish team.

The game took place in Belfast on March 28th 1903 and from the very first minute it was plain to see that Archie was well up to the task. Early on in the game, he hit the Welsh upright, then, just before half-time he came close again when according to the Freeman’s Journal “he struck the crossbar with a fine attempt”. The score was still 0-0 when the second half began in a storm of rain and hail that turned the pitch into a marshy quagmire. It made accurate passing quite a challenge for both teams, but the first to get to grips with the conditions were the Welsh players, who forced the play during the opening minutes of the half. But they could not break down the solid Irish defence, with Archie standing firm in the eye of the attacking storm.

Ireland then began to turn the tables, with a period of superb offensive play that kept the Welsh defenders incessantly busy. In the 65th minute, Archie went forward on a typically barnstorming run from defence, smashing into midfield and letting fly with a swerving, drooping shot that landed and bounced in front of the Wales ‘keeper- who let it slip through his hands and into the net.

Amid tremendous cheering from the crowd Ireland won the game, which earned them an equal share of the trophy. They may have been only ‘joint champions’ of Britain but it was still the best Ireland had ever done in the tournament. As well as helping his country to achieve that honour, Archie’s goal against the Welsh made him Ireland’s oldest ever goalscorer. That was his last international goal and, one year later, in March 1904, he played his last international match.

Archie’s retirement from football did not lead to times of quiet reflection and easy living. He became internationally famous as a strongman and vaudeville star. On his posters he was billed as “Archie Goodall, the world’s greatest international footballer, in the most wonderful and daring act in existence, Walking the Hoop!, a remarkable cross between illusion and athleticism that defies the laws of gravity and the limitations of the human body.” He travelled to America, had great success there with his performances, and only stopped his shows when he was in his sixties.

Archie died at the age of 81. His obituary in the Derby Telegraph recalled Archie’s playing days, saying “he was strong as a horse, highly intelligent and had no equal on the football field. There is no doubt that Archie Goodall was one of the most remarkable personalities the game has ever produced”

Good old Archie Goodall.